Some of you may be surprised (and some may not be surprised) to learn that I grew up rich. Or, rather, my family was rich. It wasn’t old money, inherited from a great, great grandmother. It was new, fresh. Created by my parents.

This aspect of my childhood was made apparent each time I entered one of my friends’ homes. The mother would be handing candy, toys, and the TV remote to her children, requesting peace but truly begging for purpose. The father would be in the yard, always in the yard, running his mower over the same, balding patch of grass that he ran through the night before. Even though he never smoked, and though I’ve never condoned it, it always seemed like he might smile a little more if he did. And the summer would burn bright, but their house would be cold, cold, cold. I’d shiver the whole walk home.

Back then, I didn’t know to feel remorse for the vast valley that lie between me and them. I didn’t know I had something that they didn’t. It was made clear early on that I was different. But kids don’t see difference. Everything is apples to apples. They are apples. Their friends are apples. Their friends’ family are apples. And their family is apples. But that’s the thing, there aren’t any apples at all.

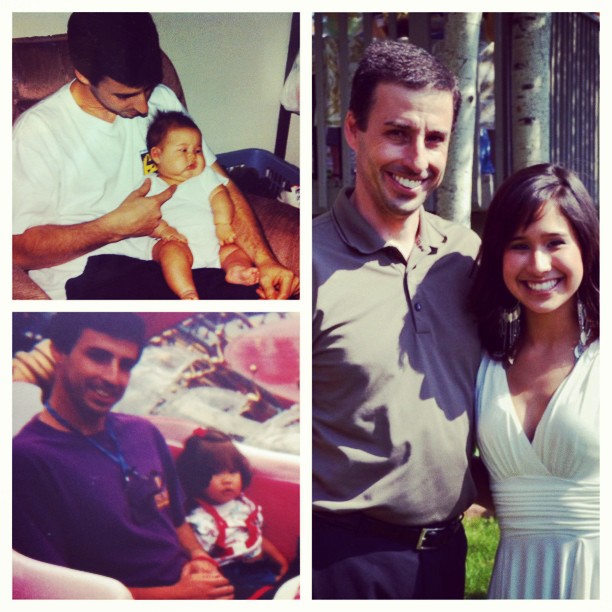

In the winter, when the power snapped off, as it did with the heavy snow, Dad would gather us around and light old candles and tell us his old stories. Mom look back and forth from the thermostat to us and demand that we add another layer to our sweater and sweat pant sets. We’d whine, but oblige. Dad would get on a roll, describing his adventures. And we’d laugh when he laughed, even if there wasn’t anything particularly funny because we wanted to feel the way he did in that moment. We wanted to be a part of those moments with him. Mom would go to bed earlier than any of us, but she’s sit next him as he crouched and flailed his hands, retelling the stories she’s heard so many times. The light didn’t have to catch them just right, the way Mom looked at Dad told us everything.

I never knew much about my parents’ finances. I had no need to. They didn’t talk about money with us, they never fought and screamed and said nasty things to each other about it. Not like other parents did. As you have gathered, I had everything I could’ve ever needed, but it didn’t keep me from asking. Suppose that was why they never discussed it with me.

As a child, you only know to want and never know what you cannot have. Mom must’ve told me at least ten times, “no” before I put back the plush that I’d just fallen in love with, she’d note the plethora on my shelves “just like it.” With big teary eyes I would hold tight to my new found friend. Finally, she’d cave a little.

“You can carry it around the store,” she’d say with a smile, “then you’ll have to say goodbye.”

This was a treat. I named, groomed, loved that stuffy for the entire thirty minutes of our companionship then, as agreed to, I’d drop it off in the basket I found it. Waving a melancholy hand as I left. When we got back home, I’d run to my room and hop on a stool to reach my shelves and hug my toys to let them know, I was so happy to have saved them from the scary super market.

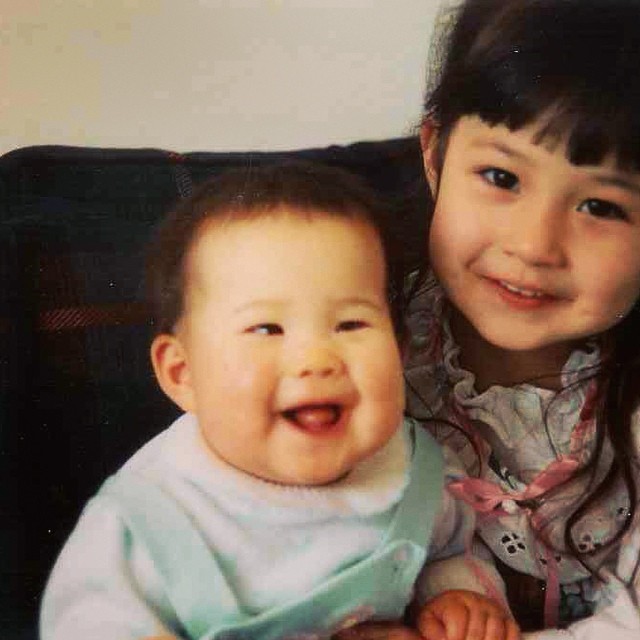

When I was little, my brothers and I would line up my animals and theirs in a march from the door of my room to theirs across the hall. Dad would come and visit us from time to time to get an update on the story. “They’re moving to California!” Would be our explanation for the mess sometimes, or “I’m just making sure they are all here,” would be mine at others. It was like counting gold coins again and again for me.

When the occasion came to gather with my friends, we usually went somewhere other than my house—something I didn’t realize until I was older—and when I arrived it would be so, painstakingly obvious the space that was between me and them; everything down to our clothes painted a contrast that I now recognize I was blind to. Everything was either slightly too-large or slightly too-small and hugged or hung accordingly. Patches covered the knees of jeans with a hem at the ankle to make the second-hand clothes fit. I remember the shame I felt for cringing at the sight of it.

Going home for me wasn’t like it was for my peers. They’d talk about how “stupid” their parents were, or how much they wanted to run away. They never did, but they’d say it enough to think they would eventually. I’d sit quietly, having nothing to add to the conversation. I guess I couldn’t have possibly understood, given the situation. For me, going home felt like being known.

We’d all pile in and Mom would return to the sewing machine at the table. I had only a little while before Mom noticed I wasn’t hard at work on memorizing the words for my spelling test. I’d run to the TV and adjust the bunny-ears until the statics was bearable. Just as I’d find the right position, Mom would call, “are you done with your homework?”

Growing up rich didn’t teach me the things you’d think it would. It didn’t teach me that money and happiness were synonymous. In fact, they seemed so far removed from one another, I’d never understood why they were so frequently paired together. But I suppose you don’t have to worry about something you have.

Once, I was downstairs with Mom, who was folding laundry. “Those don’t fit anymore,” I fibbed as I pointed to my pants.

“What do you mean ‘these don’t fit’? You wore them just the other day.” She looked them up and down to see if they’d shrunk. I was caught in my lie as soon as it began. “What is wrong with them?” She demanded.

I shook my head but she pressed. “Tell me what’s wrong with them. I don’t see any more rips. Do we need to patch it somewhere?” I shook my head again, feeling that same sense of shame bubble up over me.

“I don’t like the patches, Mom,” I said getting just enough courage to say the words, but not enough to look up from the floor. I’d worn both of the knees through and in their place were the too-light jean patches.

“What do you mean? You can’t even tell a difference?” She said, convinced. Maybe she couldn’t and maybe I couldn’t, but my friends certainly did. And then I cried. I cried out of guilt, of asking for more when I had so much. I cried from embarrassment. I cried from confusion, because I could not understand how it was that I was so very different from people who I wanted to be so like.

Mom crouched down and wiped away my tears. She pulled my chin up and said, “look at me.” In the way that only she can, she looked at me so sternly and so assuredly that I knew I’d believe whatever it was she’d tell me. “You will always be different from them. You will always have something they don’t. And you might not see it now, but it’s the most important thing for you to have. Do you know what that is?”

I shook my head, no, even though I knew. I needed her to tell me again.

“It’s not money, or stuff, or clothes,” she said as she held my jeans. “It’s character,” she said as she squeezed my hand. “You will have character, and when you have nothing else, that will be enough.”

Yes, I grew up rich. Exceptionally rich. I grew up with the only kind of wealth that’s ever mattered much to me—that of the soul. I believe with everything inside of me that money does not keep someone from being rich internally. Money is not the problem. People are. My beliefs did not come from lack of money, but from the wealth of love, encouragement, and discipline in my life.

And eventually, in my family’s story, the money followed.

Now, I can look back at those days and say today with the immovable certainty that if I had no physical wealth, I would still have my character. I would have my family, and my God. And if that isn’t being rich, then I don’t know what is.

This is such a great piece of writing, Lindsay! It’s very relatable. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you :). I’m glad you were able to relate to it!

LikeLike

You go, girl! 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you 🙂

LikeLike